Przeciążanie konstruktorów

From MorphOS Library

Grzegorz Kraszewski

Ten artykuł w innych językach: angielski

Obiekty bez obiektów potomnych

Konstruktor obiektu (metoda OM_NEW()) ma tę samą strukturę parametrów opSet co metoda OM_SET(). Struktura ta zawiera pole ops_AttrList będące wskaźnikiem na taglistę zawierającą początkowe wartości atrybutów obiektu. Implementacja konstruktora dla obiektu nie zawierającego obiektów potomnych jest raczej prosta. Na początku wywołuje się konstruktor klasy nadrzęnej. Jeżeli zwróci on wskaźnik na obiekt, konstruktor inicjalizuje dane obieku, alokuje potrzebne zasoby (np. bufory w pamięci) i ustawia początkowe wartości atrybutów zgodnie z tagami przekazanymi w ops_AttrList.

Najważniejszą zasadą przy przeciążaniu konstruktorów jest nie zostawianie nigdy częściowo skonstruowanego obiektu. Konstruktor powinien zwrócić albo kompletny i całkowicie zaincjalizowany obiekt, albo zakończyć się niepowodzeniem, ale przedtem zwrócić wszystkie te zasoby, które udało się mu zarezerwować. Jest to szczególnie istotne, jeżeli obiekt uzyskuje przydział więcej niż jednego zasobu i którykolwiek z przydziałów zakończy się niepowodzeniem (przykładowo alokacja dużego obszaru pamięci albo otwarcie pliku). W przykładzie poniżej obiekt usiłuje zarezerwować trzy zasoby nazwane umownie A, B i C.

IPTR MyClassNew(Class *cl, Object *obj, struct opSet *msg)

{

if (obj = DoSuperMethodA(cl, obj, (Msg)msg))

{

struct MyClassData *d = (struct MyClassData*)INST_DATA(cl, obj);

if ((d->ResourceA = ObtainResourceA()

&& (d->ResourceB = ObtainResourceB()

&& (d->ResourceC = ObtainResourceC())

{

return (IPTR)obj; /* success */

}

else CoerceMethod(cl, obj, OM_DISPOSE);

}

return NULL;

}

Jeżeli destruktor obiektu zwalnia zasoby A, B i C (co byłoby logiczne, skoro są rezerwowane w konstruktorze), oczyszczanie po nieudanej konstrukcji można wykonać przy jego użyciu. Taki destruktor musi być jednak przygotowany na fakt, że może mieć do czynienia z częściowo skonstruowanym obiektem. Nie może zakładać, że wszystkie zasoby do zwolnienia na pewno zostały przydzielone. Najcześciej oznacza to sprawdzenie każdego wskaźnika do zasobu na okoliczność wartości zerowej (lub innej, jeżeli zero jest prawidłowym identyfikatorem zasobu). Destruktor wywołuje następnie destruktor klasy nadrzędnej. Przykłady destruktorów z objaśnieniami znajdują się w rozdziale "Overriding Destructors".

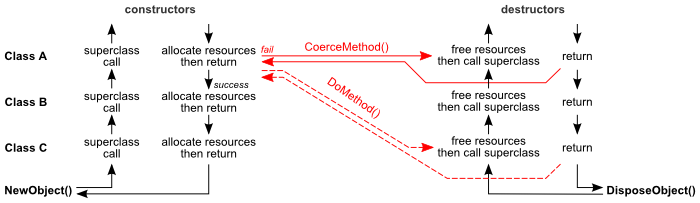

Pozostaje jeszcze otwarta kwestia funkcji CoerceMethod(). Jakie jest jej działanie i dlaczego została tu użyta zamiast zwykłego DoMethod()? Funkcja ta wykonuje metodę na obiekcie, tak samo jak DoMethod(), ale wykonuje tzw. "wymuszenie" (ang. coercion) wykonania metody ściśle określonej klasy, poprzez bezpośredni skok do jej dispatchera, zamiast do rzeczywistej klasy obiektu. Jeżeli obiekt jest klasy pochodnej względem tej, której konstruktor przeciążamy, to będą to oczywiście dwie różne klasy. Diagram poniżej ilustruje problem:

The class B on the diagram is a subclass of the class A and similarly, the class C is a subclass of B. Let's assume an object of the class C is being constructed. As every constructor calls the superclass first, the call goes up to rootclass (the root of all BOOPSI classes) first. Then going down the class tree, every class constructor allocates its resources. Unfortunately the constructor of class A has been unable to allocate one of its resources and decided to fail. If it had just called DoMethod(obj, OM_DISPOSE) it will unnecessarily execute destructors in classes B and C, while constructors in these classes have been not yet fully executed. Even if these destructors can cope with this, calling them is superfluous. With the CoerceMethod() the destructor in the class A is called directly. Then class A constructor returns NULL, which causes constructors in classes B and C to fail immediately without resource allocation attempts.

Obiekty z obiektami potomnymi

While retaining the same principles, the constructor of an object with subobjects is designed a bit differently. The most commonly subclassed classes able to have child objects are Application, and Group. The Window class is also often subclassed in a similar way. While a Window object can have only one child, specified by MUIA_Window_RootObject, this child often has multiple subobjects. The constructor should create its child objects first, then insert them into the ops_AttrList taglist and call the superclass constructor. If it succeeds, then resources may be allocated if needed. As any of the three constructor stages may fail, proper handling of errors becomes complicated. Also inserting objects created into the taglist as values of child tags (like MUIA_Group_Child) is cumbersome. Fortunately one can use the DoSuperNew() function, which merges the creation of subobjects and the calling of the superclass into one operation. It also provides automatic handling of failed child object construction. An example below is a constructor for a Group subclass putting two Text objects in the group.

IPTR MyClassNew(Class *cl, Object *obj, struct opSet *msg)

{

if (obj = DoSuperNew(cl, obj,

MUIA_Group_Child, MUI_NewObject(MUIC_Text,

/* attributes for the first subobject */

TAG_END),

MUIA_Group_Child, MUI_NewObject(MUIC_Text,

/* attributes for the second subobject */

TAG_END),

TAG_MORE, msg->ops_AttrList))

{

struct MyClassData *d = (struct MyClassData*)INST_DATA(cl, obj);

if ((d->ResourceA = ObtainResourceA()

&& (d->ResourceB = ObtainResourceB()

&& (d->ResourceC = ObtainResourceC())

{

return (IPTR)obj; /* success */

}

else CoerceMethod(cl, obj, OM_DISPOSE);

}

return NULL;

}

An important thing to observe is the fact, that DoSuperNew() merges the taglist passed to the constructor via the message ops_AttrList field and the one specified in the function arguments list. It is done with a special TAG_MORE tag, which directs a taglist iterator (like NextTagItem() function) to jump to another taglist pointed by the value of this tag. Taglist merging allows for modifying the object being constructed with tags passed to NewObject(), for example adding a frame or background to the group in the above example.

The automatic handling of failed child objects works in the following way: when a subobject fails, its constructor returns NULL. This NULL value is then inserted as the value of a "child" tag (MUIA_Group_Child) in the example. All MUI classes able to have child objects are designed in a way that:

- the constructor fails if any "child" tag has a NULL value,

- the constructor disposes any successfully constructed child objects before exiting.

Finally DoSuperNew() returns NULL as well. This design ensures that in case of any fail while building the application, all objects created are disposed and there are no orphaned ones.